The historian entrusted with interpreting the Pearl Harbor attack sites and the USS Arizona Memorial tells how a new project to find more accurate data on the Arizona’s dead is revealing the human stories behind the history.

By Daniel Martinez

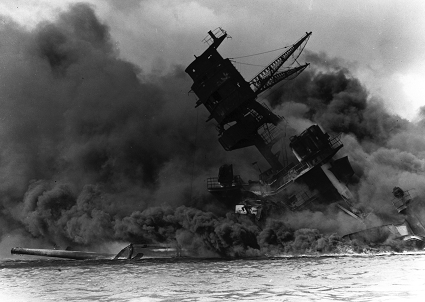

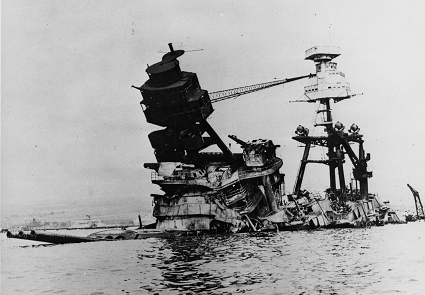

By mid-morning of December 7, 1941, the fate of the USS Arizona and its crew was no longer in doubt. Fires roared from the amidships to the bow. Thick black smoke billowed out in large volumes, cloaking the details of the vessel’s terrible destruction. It was evident that there were few survivors of the celebrated battleship Arizona. Three days later the fires went out and the mangled remains of the ship gave mute testimony to the successful attack on the Pacific Fleet.

Over the next few days, Pearl Harbor and its survivors began to restore order out of the chaos that was brought about by the raid. The command soon understood the losses that Arizona had suffered. She had lost more men than any warship in United States Naval history. Of the 1,514 men attached to the ship’s company, 1,177 were killed. Of the marine detachment of 88 men, only 15 survived. The math was horrifying; 77.7% of the crew was dead. Only 337 of the crew survived. Most were from the ship and a small number were on leave, liberty, or detached duty.

A week later a young ensign named Joe Langdell was having breakfast at Bachelor Officers Quarters when a naval officer interrupted the meal by shouting out: “Is there an officer here from the Arizona?” Joe raised his hand. Langdell was ashore during the attack, assigned to the Fleet Camera Party. He was aware the ship was lost but had no idea what had happened to his shipmates. The officer took him aside and explained his task. Joe was to lead a party of some 20 men, most of them survivors from the ship, to recover bodies. They were chosen because they were familiar with the ship and its crew. This knowledge could be helpful in the duty assigned to them. The men marched down to the landing and got into a large whaleboat. They were issued sheets and pillowcases to collect human remains.

Author Paul Stillwell, noted in his book, Battleship Arizona: An Illustrated History: “On the other hand, the emotional impact of seeing dead shipmates was even more profound than would be the case for men who had never known the crew of the USS Arizona. The recovery party wrapped the complete corpses up in sheets and took them to a waiting motor launch for further transfer. The men retrieved portions of bodies and sometimes swept up ashes; storing them in pillowcases for the trip to the cemetery…. The memory of those days has bothered him [Langdell] many times since then. He thinks of the many who would now be grandfathers but never got the chance.”

In the weeks that followed, the navy moved forward in retrieving the personal effects of the officers and the removal of the dead. A total of 235 bodies were found and buried primarily at the newly established cemetery at Halawa Valley.

Officer country [maritime slang for the officers’ quarters aboard a ship] was located in the aft section of the ship. This area was virtually untouched by the fatal explosion of the forward magazines. Pay records [likely to be found in the officers’ area] were vital. Many families had been notified that their loved one was either missing in action or declared dead. Without these records, the families could not receive the money owed to them. Dealing with grief was hard enough without the additional financial burden the dependents would suffer if they couldn’t be paid or receive Navy Relief.

These valuable documents would later be preserved in the service jackets [folders containing military personnel’s service records] of the fallen and those who survived, becoming part of a legacy of those who served on the Arizona. Chief Commissary Steward Ralph Byard took a personal and professional interest in preserving these records. His meticulous work helped preserve the papers of his fallen shipmates. Arizona survivor Yeoman Jim Vlach went to work compiling a muster role of the 350 men who survived, but he could only confirm 80 names. In February of 1942, salvage divers found the ship’s muster roll in the executive officer’s office. With those records in hand an accurate count of the dead and living could be constructed.

Twenty years later the USS Arizona Memorial was dedicated on Memorial Day, May 30, 1962. A key feature of the Memorial is the shrine room wall. Alfred Preis understood the importance of listing the names of those who lost their lives. He designed a wall made of Vermont marble and had each individual casualty engraved with name and rank or rate. How the names were collected and what database was used is still a mystery. The wall was replaced twice in its history. Verification of those names has been the grist of controversy and confusion.

In 2015, after much discussion about historical accuracy regarding the names on the replacement wall, Superintendent Paul DePrey, Chief Historian Robert Sutton, and I made a decision. A comprehensive research study on the casualties of the USS Arizona would be conducted at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis, Missouri. The center is operated as a division of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). The project was daunting to say the least.

The first order of business was to put together a comprehensive research plan, beginning with finding an expert. Enter Mr. Mike Wenger. Mike is one of the finest researchers of World War II documents in the nation and his specialty is personnel records. Over the years, Mike has been contracted to do a number of research projects for the monument.

With completion of the research plan, the team traveled to St. Louis in January of 2015. During that time, discussions with Mr. Eric Kilgore and Mr. Whitney Mahar began in an effort to coordinate the research and scanning of the Arizona crew records.

The first trip to the record center in St. Louis would determine how this project would unfold…. My meetings with the officials at NARA went well. I soon found out that a research project of this size was unprecedented in the history of the records center.

From the start, there were a number of questions that needed to be answered. How do you organize and pull 1,177 service jackets from the millions of records that exist in their holdings? How many staff members would be needed to observe the work being done by the research team and how would the records be dispensed? How much workspace would the National Park Service research team require? And finally, once the records had been reviewed and tabbed, how much time would be needed for staff to prep the records for scanning? (Prepping includes the process of flattening the documents and determining their condition. If the record is too fragile, Mylar sleeves are used to protect the document.) Other factors would come up later as we began the project in mid-March.

Another criterion was the cost. The funding source for such a robust research project was vital. Could diminished NPS funds be used or was there an alternative source? We were fortunate to have the interest and support of Pacific Historic Parks, the monument’s non-profit association whose funds are primarily raised from sales in the visitor center’s bookstore. President and CEO Gene Caliwag and CFO Aileen Utterdyke were briefed about the project and committed their financial support. It’s safe to say that without PHP’s support, the USS Arizona Casualty Project would not have happened.

It became evident that Mike Wenger’s expertise would play a major factor in the planning and execution of this project. Over the years he has developed relationships with the NARA staff and understands the culture of this National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis. He paved the way for success.

Upon my return from St. Louis, my discussions with Mr. Wenger now centered on developing a research team. What would it take to scan thousands of documents? How many people were needed to scan these records? How would they be organized?

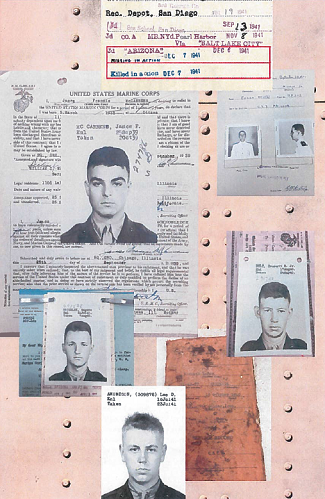

During our visit we scanned and reviewed more than 30 service jackets (commonly referred to as “bricks” because the paper record holder is red and square). After looking into these records and seeing what information they contained it dawned on me that this project was not just about the accuracy of the subjects’ name or rate/rank. It was also about an individual’s life and death.

These records spoke to me. They disclosed the subjects’ place of birth, their parents’ names, where they grew up, went to school, and the age when they enlisted, some as young as 17 years of age. Some of the men were single; some were married with children. One young Marine reported to the Arizona on December 6, 1941, and would perish in less than 24 hours. One sailor’s birthday was on December 7.

And the letters inside these records, handwritten to President Franklin D. Roosevelt or to Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, pleading and begging as to where their boy, husband, or father might be. For a great many dependents, the only communication was a telegram or letter declaring them “missing in action.” This left loved ones to wonder or speculate: were they dead or alive? I cannot think of another phrase that could be so emotionally troubling. Oh yes, there was one… “Declared dead.” Those messages came too.

One can only imagine the fear that Americans felt when the Western Union Telegram truck drove down their street in 1941.

Order a copy of our 120-page special issue, PEARL HARBOR REMEMBERED.

Photos, from top:

• A National Park Service team scanned these and other images and records from the service folders of USS Arizona crewmen killed in the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941. The work will continue as part of the USS Arizona Casualty Research Project. PACIFIC HISTORIC PARKS

• The battleship USS Arizona (BB-39) burns wildly after the Japanese air attack and the explosion of the ship’s forward magazine. WWII VALOR IN THE PACIFIC NATIONAL MONUMENT

• Arizona as she appeared after the fires were extinguished. The work of recovering human remains and important records began. WWII VALOR IN THE PACIFIC NATIONAL MONUMENT

• Workers complete corrections to the wall bearing the names of the Arizona’s killed, in the shrine room of the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor. This round of corrections to the wall was completed in November 2014. PACIFIC HISTORIC PARKS

• A “Remember Pearl Harbor” pin worn on the US home front during World War II. The memory of the December 7 attack became a powerful inspiration to Americans as their nation joined the global war against the Axis powers. AMERICA IN WWII COLLECTION

Links to More Information

PEARL HARBOR DEAD

See the list of Pearl Harbor dead we published in our 2011 special issue Pearl Harbor Stories [out of stock].

USS ARIZONA MEMORIAL

Read author Allyson Patton’s article on visiting the site.

VALOR IN THE PACIFIC

Find history and more on the official website of World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument, home of the USS Arizona Memorial.

http://www.nps.gov/valr/index.htm

PACIFIC HISTORIC PARKS

Check out the website of the private non-profit partner of World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument.

http://www.pacifichistoricparks.org/

FOLLOW US »