On a torpedoed troop ship in the icy North Atlantic, four army chaplains made a heroic choice to put other men’s survival before their own.

by Richard Sassaman

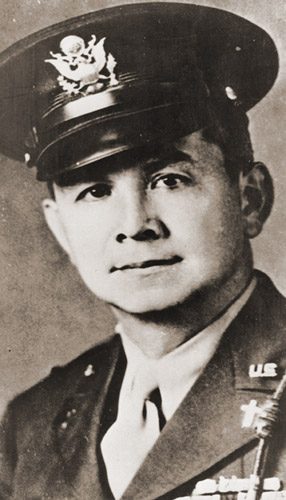

George L. Fox, a Methodist minister from Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts. (National Archives)The US Army Transport Dorchester was crammed with nearly 1,000 American soldiers as it pulled out of port at Saint John’s, Newfoundland, on January 29, 1943. Just a few months earlier, she had been a pleasure ship, a luxury liner that had cruised the East Coast for 16 years. A full load for her in those heady days was 341 passengers. Then came the reality of a world at war, and rebirth as a troop transport. Her days of whisking away the wealthy for dalliance and diversion were gone for good. Now she was bound for the US Army base in Narsarssuak, Greenland.

George L. Fox, a Methodist minister from Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts. (National Archives)The US Army Transport Dorchester was crammed with nearly 1,000 American soldiers as it pulled out of port at Saint John’s, Newfoundland, on January 29, 1943. Just a few months earlier, she had been a pleasure ship, a luxury liner that had cruised the East Coast for 16 years. A full load for her in those heady days was 341 passengers. Then came the reality of a world at war, and rebirth as a troop transport. Her days of whisking away the wealthy for dalliance and diversion were gone for good. Now she was bound for the US Army base in Narsarssuak, Greenland.

Among the thousand packed aboard the 367-foot-long Dorchester as she steamed through the North Atlantic were four chaplains and close friends who were as much a cross section of America as any platoon in a Hollywood movie. There was John Washington, a Catholic priest from New Jersey; Clark Poling of Michigan, a Dutch Reformed pastor whose father had been a chaplain in World War I; Alexander Goode, a Pennsylvania rabbi and son of a rabbi; and George Fox, a Methodist minister from Vermont who served as his state’s American Legion chaplain.

Just a few days out to sea, these four chaplains suddenly faced the climactic moment of their ministries after a German torpedo fatally punctured the Dorchester. The chaplains spent the last 20 minutes of their lives calming the terrified men around them, helping the injured into lifeboats, and even giving their own life jackets to men who had none. Then, with no way to save themselves, they bravely locked arms and together went down with the Dorchester.

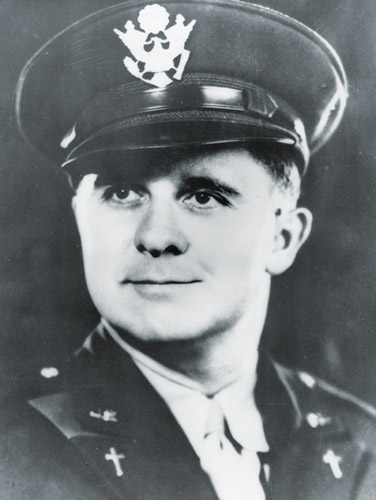

Alexander D. Goode, a Jewish rabbi from Washington, DC. (National Archives)

Alexander D. Goode, a Jewish rabbi from Washington, DC. (National Archives)

Over the next 65 years, books, television shows, and radio documentaries told the chaplains’ story. All four were posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and Distinguished Service Cross. They were honored with a US postage stamp (issued in 1948), a viaduct spanning Ohio’s Tuscarawas River (built in 1949), a special Congressional medal for heroism (awarded posthumously in 1961), stained-glass windows at the Pentagon, West Point, and Fort Snelling, Minnesota, and memorials and chapels here and there across the United States.

“Because I grew up with this story, and the stamp, and visits from my aunt, who took over the ministry of my uncle in Vermont, I’d [wondered] ‘Is this real, or not?” says David Fox-Benton, nephew of Chaplain Fox. “Did it really happen?’” Fox-Benton set about finding his answer, and discovered the four chaplains and their heroic act were very real indeed.

Fox was the oldest of the chaplains. He had first entered the army in 1917, joining the ambulance corps just after the United States entered World War I. He was only 17, but told recruiters he was 18. He earned a Silver Star, a Purple Heart, and the French Croix de Guerre. After Pearl Harbor was attacked, he reenlisted, joining the Army Chaplain Service the same day that his son Wyatt enlisted in the Marine Corps.

John P. Washington, a Catholic priest from Newark, New Jersey. (National Archives)Goode ended up an army chaplain because the navy had no openings. “Rabbi Goode was an amazing man,” says Fox-Benton, whose research led him to co-found the Immortal Chaplains Foundation—a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the legacy of the four chaplains—of which he is the executive director. Goode “had a PhD in Arabic studies, was fluent in Arabic, and he envisioned working to bring Arabs and Jews together. He and my uncle were the only two who knew each other before everyone met on the ship. They were close friends at Harvard University’s chaplain school.”

John P. Washington, a Catholic priest from Newark, New Jersey. (National Archives)Goode ended up an army chaplain because the navy had no openings. “Rabbi Goode was an amazing man,” says Fox-Benton, whose research led him to co-found the Immortal Chaplains Foundation—a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the legacy of the four chaplains—of which he is the executive director. Goode “had a PhD in Arabic studies, was fluent in Arabic, and he envisioned working to bring Arabs and Jews together. He and my uncle were the only two who knew each other before everyone met on the ship. They were close friends at Harvard University’s chaplain school.”

Like Goode, Washington had been turned down by the navy, because of his eyesight; as a child, he’d been shot in the eye accidentally with a BB gun. Poling had decided to become a minister after breaking his wrist playing football in college.

In the 1990s Fox-Benton began interviewing survivors of the Dorchester. “I was so struck by the fact that…the first sergeant of the ship was the first one who said it about the chaplains, ‘These men were always together. They carried their faith together,’” he says. “Remember, this was 1943. Protestants didn’t talk to Catholics back then, let alone either of them talk to a Jew. And yet here they were, always together, and they loved each other. The men said it didn’t matter which service they went to, that the chaplains always made them feel welcome and cared for. They were remarkable for 1943, way ahead of their time.”

The submarine that put the Dorchester and the chaplains into the history books surfaced on the night of February 2–3. The Dorchester was steaming through the North Atlantic in the middle of the SG-19 convoy—six ships that included the freighters Biscaya and Lutz, the 165-foot Coast Guard cutters Comanche and Escanaba, and the 240-foot Coast Guard cutter Tampa. In 36-degree water and colder air, the Dorchester was wallowing through the sea about 150 miles from Greenland, getting coated with ice and not managing even its usual slow speed of about 10 knots. By morning the convoy would be within range of air cover, but that would be too late. It was already being tracked by U-223, one of 13 German submarines in the Haudegen (War Horse) group assigned to a 300-mile arc northeast of Newfoundland.

Clark V. Poling, a Dutch Reformed Church minister from Schenectady, New York. (National Archives)The Dorchester’s captain, Hans Danielson, was aware U-boats operated in these waters, and ordered the men to sleep in their clothes with lifejackets nearby, but many—especially those near the hot engine rooms—disobeyed. No one ever saw the U-223, even though it was running on the surface. “The U-boat could barely make out the configuration of the convoy,” Fox-Benton says. “It expected them. It knew they were coming. The captain, [Oberleutnant Karl-Jürgen] Wächter was his name, stood on the conning tower, alone, peering with his binoculars” from about 1,000 yards away. “He ordered a fan of three torpedoes fired, one of which hit the Dorchester amidships.”

Clark V. Poling, a Dutch Reformed Church minister from Schenectady, New York. (National Archives)The Dorchester’s captain, Hans Danielson, was aware U-boats operated in these waters, and ordered the men to sleep in their clothes with lifejackets nearby, but many—especially those near the hot engine rooms—disobeyed. No one ever saw the U-223, even though it was running on the surface. “The U-boat could barely make out the configuration of the convoy,” Fox-Benton says. “It expected them. It knew they were coming. The captain, [Oberleutnant Karl-Jürgen] Wächter was his name, stood on the conning tower, alone, peering with his binoculars” from about 1,000 yards away. “He ordered a fan of three torpedoes fired, one of which hit the Dorchester amidships.”

The torpedo exploded along the starboard side just before 1 A.M., immediately cutting all power aboard, including the steam needed for the abandon-ship alarms that Danielson ordered three minutes later. Survivor Michael Warish told Fox-Benton, “Lights went out, and steam pipes broke, and [there was] screaming. Bunks tripledeck high, they went down like a deck of cards. A very strong odor of gunpowder, and sometime after that, of ammonia. I was trapped.

I broke my right ankle. A bunk rail had me pinned down on my right foot. There was debris in back of my legs. My head was bleeding, and I had to talk to myself to fight off the panic.”

The chaplains started organizing the men. “They handed out life jackets, [helped people] put them on, and then led them to a place where they could jump off and not be hurt,” Fox-Benton says. “The chaplains, without any hesitation, just simply took off their own life jackets and placed them on the next man who was waiting there.”

Warish made his way onto the tilting deck, where he noticed some people at the back of the ship. “I was so happy that I’d got somebody to go abandon ship with I must have lit up like a 100-watt light bulb. I went down there [and found] 10 or 11 men. The chaplains opened up with prayer, and I saw they were not going to abandon ship. They were going to hold our last service.”

The Dorchester sank in just 18 minutes. “That’s a very fast sinking,” Fox-Benton says. On its way down, the ship followed U-223, which had quickly descended about 130 feet after Wächter saw his torpedo hit its target. The sub “went down and stayed down for probably six hours or so,” says Fox-Benton. The Germans “heard the ping ping of the sonar, so they knew they were being looked for” by the rest of the convoy.

Meanwhile, the Tampa hurried the two freighters away from the scene, and Comanche and Escanaba, in what the Coast Guard considers number 4 of the top 10 rescues in its history, saved 229 men from the icy water. Because most of the survivors had been weakened by the cold, the Escanaba crew tried a new rescue technique involving “retrievers,” swimmers in wet suits who swam to victims and tied lines to them so they could be hauled aboard the cutters.

Fox, Poling, Washington, and Goode join arms and pray together as GIs leave the sinking Dorchester. Having given their life jackets to men who had none, the chaplains went down with the ship. (Courtesy of the Chapel of the Four Chaplains)U-233 survived the day, and continued trolling for Allied ships until March 30, 1944, when it was sunk by depth charges in the Mediterranean north of Palermo, Italy, by two British destroyers and two escort destroyers. Of the 50 men on board, 23 died. “The others were brought to the United States as prisoners of war on the Queen Mary, which is where we have our [Immortal Chaplains Foundation] memorial chapel and sanctuary and offices,” Fox-Benton says. “Isn’t that ironic?” [The RMS Queen Mary is permanently moored at Long Beach, California.]

Fox, Poling, Washington, and Goode join arms and pray together as GIs leave the sinking Dorchester. Having given their life jackets to men who had none, the chaplains went down with the ship. (Courtesy of the Chapel of the Four Chaplains)U-233 survived the day, and continued trolling for Allied ships until March 30, 1944, when it was sunk by depth charges in the Mediterranean north of Palermo, Italy, by two British destroyers and two escort destroyers. Of the 50 men on board, 23 died. “The others were brought to the United States as prisoners of war on the Queen Mary, which is where we have our [Immortal Chaplains Foundation] memorial chapel and sanctuary and offices,” Fox-Benton says. “Isn’t that ironic?” [The RMS Queen Mary is permanently moored at Long Beach, California.]

In the late 1990s, Fox-Benton traveled several times to Kiel, Germany, and spoke with three of the six U-223 crew members who were still alive, including the chief of munitions who had handled the torpedo that sank the Dorchester. “That was so moving, you killed my uncle some 50 years ago,’” Fox-Benton says. “They were cautious at first, until I said ‘I’m coming not to blame you, but to me there are two sides to the story.’ Just as the chaplains reached out to each other, I felt that as a representative of the families of the chaplains, I wanted to reach out to [the German crew], because I felt that the chaplains would have forgiven them….

“When I was interviewing the U-boat crew, they just would cry. The men had never told their families this story. They realized that when they hit that ship, there were men dying. They cheered the first moment, and then it just got very silent, and they felt terrible after that. These were Germans—they were not Nazis—young boys, 17, 18, 19 years old, forced to do it or they would have been shot, pretty much like in the movie Das Boot. The U-boat crews did what they had to do, but they didn’t like it very much.”

The United States Postal Service honored the four chaplains with this stamp in 1948. (National Archives)Since 1999, the Immortal Chaplains Foundation has awarded a Prize for Humanity “to those who risked all to protect others of a different faith or ethnic origin.” The first honoree was Charles W. David, Jr., a black Coast Guard mess attendant from the Comanche who died after saving several men. “I call him ‘the fifth man’ in this story,” Fox-Benton says. “He plunged into that freezing water to save men from the Dorchester, pulling out men, sometimes two at a time, who were white. Even though when they had pulled into port [in Saint John’s], he couldn’t even go into the same club as his shipmates. Then he died himself from exposure. That’s a story that needs to be kept alive.”

The United States Postal Service honored the four chaplains with this stamp in 1948. (National Archives)Since 1999, the Immortal Chaplains Foundation has awarded a Prize for Humanity “to those who risked all to protect others of a different faith or ethnic origin.” The first honoree was Charles W. David, Jr., a black Coast Guard mess attendant from the Comanche who died after saving several men. “I call him ‘the fifth man’ in this story,” Fox-Benton says. “He plunged into that freezing water to save men from the Dorchester, pulling out men, sometimes two at a time, who were white. Even though when they had pulled into port [in Saint John’s], he couldn’t even go into the same club as his shipmates. Then he died himself from exposure. That’s a story that needs to be kept alive.”

During a speech at that award ceremony, in Minneapolis, Archbishop Desmond Tutu spoke of the four chaplains. “These four wonderful men…lived out their sermons by dying.” When their ship sank, he continued, “they should have disappeared from the face of the earth, as they did physically, as they went down into the icy cold waters of the Atlantic. But isn’t it extraordinary that now the opposite has happened, that instead of oblivion and forgetfulness, they receive glory and honor.”

To view captions and photo credits for the images above, hover your cursor over the images.

This article originally appeared in the February 2008 issue of America in WWII. Find out how to order a copy of this issue here. To get more articles like this one, subscribe to America in WWII magazine.

FOLLOW US »