On the eve of World War II, the German American Bund insisted the Nazi salute was as American as apple pie.

By Mark D. Van Ells

Jesus Christ and Adolf Hitler. Only a Nazi would have dared to compare. “Hitler is the friend of Germans everywhere,” one girl in a Nazi youth camp remembered being told, “and just as Christ wanted little children to come to him, Hitler wants German children to revere him.” The comment may hardly sound shocking, considering the Nazi mindset, but the girl who heard it wasn’t in Düsseldorf or Stuttgart or Berlin. She was in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In the heartland of America, American children were being indoctrinated into Nazism as the Nazis prepared to take over Europe.

The youth camps were run by an organization of German immigrants in the United States to cultivate a loyal Nazi following in their adopted homeland. All but forgotten today, the group known as the German American Bund (bund is German for “alliance”) was one of the most controversial political groups of the politically uncertain 1930s. Nazi ideology taught that all Germans were united by blood and that the descendants of German emigrants around the world needed to be awakened to their racial duties in support of Hitler. The United States, 25 percent of whose population traced ancestry back to Germany, was a tempting target for Nazi recruiters. Forty-three percent of the population of Wisconsin, a state noted for its beer and bratwurst, was either German-born or first-generation German American in 1939. Nazis believed those German Americans could be awakened to their cause.

The youth camps were run by an organization of German immigrants in the United States to cultivate a loyal Nazi following in their adopted homeland. All but forgotten today, the group known as the German American Bund (bund is German for “alliance”) was one of the most controversial political groups of the politically uncertain 1930s. Nazi ideology taught that all Germans were united by blood and that the descendants of German emigrants around the world needed to be awakened to their racial duties in support of Hitler. The United States, 25 percent of whose population traced ancestry back to Germany, was a tempting target for Nazi recruiters. Forty-three percent of the population of Wisconsin, a state noted for its beer and bratwurst, was either German-born or first-generation German American in 1939. Nazis believed those German Americans could be awakened to their cause.

World War I had been traumatic for Germans on both sides of the Atlantic. In the United States, a wave of anti-German hysteria had swept through the nation. Fear spurred by government propaganda led some to attack what they believed was the enemy in their midst, even though there was little evidence to justify their fears. So-called superpatriots maligned German culture. Some localities banned German music and instruction in the German language. Sauerkraut became “liberty cabbage.” There were reports of dachshunds being attacked, and German-language books being hauled out of libraries and burned in the street. Some Germans endured humiliations such as being forced to kiss the American flag in public, being spied upon by their neighbors, and in some cases even being attacked. In Illinois, one German immigrant was killed by a mob. Many German Americans hid their ethnic identity. What remained of the public German-American community grew insular, defensive, and wary of outsiders.

After the war, another wave of German immigrants came to America. Most assimilated successfully, but some did not. These maladjusted new arrivals were German fascists, described by historian Sander Diamond as “self-proclaimed émigrés” who feared “proletarianization” in Germany’s unstable new democracy. They had experienced the humiliation of Germany’s wartime defeat and occupation, and the social and political chaos that reigned there afterward. Many were young, middle-class professionals, and some had participated in street fighting against socialists and communists. Once in America, these fascists formed political groups like the Teutonia Association, founded in Detroit in 1924.

After the war, another wave of German immigrants came to America. Most assimilated successfully, but some did not. These maladjusted new arrivals were German fascists, described by historian Sander Diamond as “self-proclaimed émigrés” who feared “proletarianization” in Germany’s unstable new democracy. They had experienced the humiliation of Germany’s wartime defeat and occupation, and the social and political chaos that reigned there afterward. Many were young, middle-class professionals, and some had participated in street fighting against socialists and communists. Once in America, these fascists formed political groups like the Teutonia Association, founded in Detroit in 1924.

Just four months after Hitler came to power in January 1933, Nazi groups in the United States merged to form the Friends of the New Germany. The involvement of German nationals in the organization caused friction between Berlin and Washington, so in 1936 it was reorganized as the German American Bund and was to consist only of American citizens of German descent. Headquartered in New York, the Bund was led by Fritz Kuhn, a chemical engineer from Munich who had served in the German army during the war. Dubbed the “American fuehrer” in the press, he arrived in America in 1928, settling first in Detroit and then in New York. He became a citizen in 1934.

Not officially part of the Nazi party, the Bund behaved as if it were. It operated on the Nazi leadership principle, which demanded absolute obedience to superiors. Like Germany’s Nazi party, the American Bund divided its territory—the United States—into regional districts, and created a youth program and a paramilitary Order Division. Members donned uniforms with brown shirts and jack boots eerily like those of Germany’s Nazis. Despite their foreign appearance, members considered themselves to be loyal, patriotic Americans who were strengthening their adopted homeland, protecting it from Jewish-communist plots and black cultural influences such as jazz music. The Midwestern regional leader George Froboese of Milwaukee described the Bund as “the German element which is in touch with its race but owes its first duty to America.” To avoid another clash between Germany and America, it urged US neutrality in European affairs.

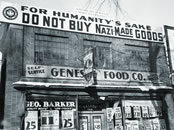

The Bund made far more enemies than friends in the United States. Socialists and communists immediately opposed it. So did Jewish Americans, who organized a boycott of products from Nazi Germany (the Bund, in turn, organized a boycott of Jewish merchants and harassed Jewish and communist groups). In Washington, Congressman Samuel Dickstein of New York began an investigation of Nazism in America. The Bund also attracted the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The German-American reaction to Hitler and the Bund was mixed. Most supported American neutrality, and many were glad to see the revival of Germany and were angry about the Jewish boycott of German goods. But they were also uneasy about Hitler. Some tried to be cautiously optimistic. The Milwaukee Sonntags-post argued in 1933, for example, that “the Hitler dictatorship represents for the moment the most efficient and expedient concentration of the united will of the German nation.” Any hopes German Americans may have placed in Hitler would soon be dashed. Nazi behavior overseas and the presence of the Bund in America would soon revive German Americans’ deepest fear: a repeat of World War I’s anti-German hysteria.

The German-American reaction to Hitler and the Bund was mixed. Most supported American neutrality, and many were glad to see the revival of Germany and were angry about the Jewish boycott of German goods. But they were also uneasy about Hitler. Some tried to be cautiously optimistic. The Milwaukee Sonntags-post argued in 1933, for example, that “the Hitler dictatorship represents for the moment the most efficient and expedient concentration of the united will of the German nation.” Any hopes German Americans may have placed in Hitler would soon be dashed. Nazi behavior overseas and the presence of the Bund in America would soon revive German Americans’ deepest fear: a repeat of World War I’s anti-German hysteria.

The Bund used several methods to try to awaken German Americans to Nazism. One was to infiltrate existing German ethnic clubs. The Bund hoped to Nazify German-American cultural life as Hitler had done under his policy of “political coordination.” The infiltration instead tore German-American communities apart. The Bund then tried to take control through intimidation. When the Wisconsin Federation of German-American Societies voted to ban displays of the swastika at cultural events in 1935, for example, Bund members threatened anti-Nazi delegates. The meeting became so heated that the police were called to restore order. Bund harassment of anti-Nazi Germans continued, and the Wisconsin federation president once received an anonymous letter saying “It is a very poor bird that dirties its own nest.”

One way the Bund promoted its cause was by sponsoring meetings and rallies, well-publicized events in which leaders outlined Nazi ideology and members distributed propaganda. Uniformed members gave the Nazi salute and shouted “Heil Hitler” as the Order Division kept a stern watch over the proceedings. There was fiery rhetoric aimed at Jews, communists, and certain politicians. Bund leaders lambasted President Franklin Roosevelt, calling him “Franklin Rosenfeld” and criticizing his “Jew Deal” social programs.

The Bund took care to display patriotism for America during its gatherings. George Washington’s birthday was a common occasion for Bund rallies. On stage, the American flag and portraits of Washington appeared side by side with the swastika. Both countries’ national anthems were played.

Bund rallies frequently became public spectacles. Protesters were a common sight, sometimes appearing in numbers comparable to the Bund members in attendance. Violence seemed all but inevitable. In Milwaukee in 1938, riots broke out at two separate Bund rallies. “Hecklers arose to break up the meeting,” the Milwaukee Journal reported of a Washington’s birthday rally in February. “The order division went to work, gloved fists flying.” One heckler lost several teeth in the melee. A month later, violence erupted again when a communist rushed the stage during a rally, enraged by the sight of children in Nazi youth uniforms.

Children were an important part of the Bund. Members sent their children to places such as Camp Hindenburg in Wisconsin each summer to participate in a youth program the Bund compared to boy and girl scouting. The camps were also gathering places for adult activities—everything from picnics to rallies. At these camps, children dressed in Nazi uniforms and drilled military-style, with marching, inspections, and flag-raising ceremonies. Although the Bund denied it, children were taught Nazi ideology.

The rise of the Bund stimulated considerable discussion in America. A few homegrown racist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, the Christian Enforcers, and the Silver Shirts (who sniped that democracy was “strictly kosher)” found common ground with the anti-Semitic, white-supremacist Bund. Most Americans, however, objected to the Bund’s racist and undemocratic ideology, and the fact that the Bund rose to prominence just as Hitler began expanding German control in Europe raised other concerns. The Bund seemed to most Americans like a dangerous foreign element, perhaps a secret Nazi fifth column in the United States. By 1938, the anti-fascist movement broadened to encompass a diverse coalition ranging from communists to veterans groups.

German Americans were torn. Some German clubs had spoken out against the Bund early on, but others resisted public criticism of the organization, fearing that a divided German community would be subject to further cultural erosion. But by 1938, anti-Bund sentiment had grown so strong that German-American leaders concluded they either had to dissociate themselves completely from the Bund or run the risk of being branded Nazis themselves. In 1938, the Wisconsin Federation of German-American Societies issued a statement declaring it had “nothing whatsoever to do with the propaganda of racial hatred and religious intolerance fostered by the Volksbund [literally, the people’s alliance—the German American Bund].” The federation claimed that the average German American was “strongly opposed to the Nazi doctrines of hate” and pleaded “America, please take notice!”

The Wisconsin federation backed up its words with action. In 1939, with the help of some in the business community, it acquired the lease to Camp Hindenburg, renaming it Camp Carl Schurz in honor of the 19th-century German-American political leader and turning it into its own youth camp. Federation president Bernhard Hofmann stated that children would be instructed there in Americanism and that there would be “no flag but the stars and stripes.” Froboese claimed the site had been “stolen,” stating “I am glad they had the decency to abandon the name Camp Hindenburg.” The Bund meanwhile obtained another site, just a mile to the south. These and other rival German-American camps operated around Milwaukee for several years.

As the 1930s came to a close, various problems had begun to take a serious toll on the Bund. The Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939 took the fire from the Bund’s anti-communist rhetoric. By the end of the year, Kuhn had been jailed for illegal use of organizational funds. Protests against the Bund continued as well, including the bombing of its Chicago offices in July 1940. The Bund developed a bunker mentality, holding its 1940 national convention secretly among three Midwestern camps. Although the Bund continued to speak out against the Jewish boycott and the “tories and internationalists” trying to provoke war with Germany, press coverage of the Bund tapered off as the group declined and public fear of domestic Nazism waned. Hundreds of dispirited Bund members returned to Germany.

When Hitler declared war against the United States four days after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Bund members found themselves stranded in enemy territory. Federal agents seized Bund records. Many of its members faced denaturalization proceedings and imprisonment. In a letter to the Bund’s lawyer, Froboese, who had risen from Midwestern regional leader to become the Bund’s national leader just weeks earlier, offered his assessment of the organization’s brief but tumultuous existence:

True it is that we made mistakes especially in the field of what you call “mental psychology.” Still, I would like to again emphasize, that I never looked upon the [Bund] as an offensive organisation. From the beginning it was a defensive movement. We have never been a cause, but instead have always been a reaction to a cause…. We always stood with both feet on American soil and in the final analysis of all of our doings, had only the very interests of this our America at heart.

In 1942 Froboese was issued a subpoena to testify before a New York grand jury concerning Bund activities. En route to New York, he got off the train in Waterloo, Indiana, and committed suicide by laying his head on the tracks in front of an oncoming train.

German Americans continued to emphasize their American-ism after the Pearl Harbor raid. “We appeal to the public not to think that everything German must be Nazi,” declared the Wisconsin Federation of German-American Societies. “We are not covering any aliens…[and] will not stand for anything that is against this country.” In New York the Loyal Americans of German Descent claimed that World War II “throws a searchlight” on German Americans and that “failure to distinguish between loyal Americans and Nazi sympathizers can create disaster.” In 1942 American Legion magazine featured the article “I Killed Americans in 1918, but Now I Fight for America.” The author called his US citizenship oath “sacred” and stated that immigrants such as he “must rally in defense of honor, family, and German-America.” Indeed, many German Americans served, fought, and died in defense of the United States during the war.

The emphasis on Americanism paid off, and a revival of anti-German hysteria did not occur. There were some unfortunate incidents of violence and prejudice against Germans during World War II, but they were not widespread. The extent of the government’s internment of German Americans during the war is hotly debated among scholars, but it was indisputably small in comparison to the internment of Japanese Americans. Most Americans seemed to make a distinction between what they believed were good Germans and bad Germans, and America became a refuge for many German intellectuals fleeing Nazi rule. In the Pacific, one of the troops’ favorite generals was German-born Walter Krueger, commander of the US Sixth Army. Actress and USO entertainer Marlene Dietrich, also born in Germany, was even more popular with the average GI than Krueger.

For all its prominence and bluster, the Bund involved only a small portion of the German-American community. Precise membership figures are not known. Estimates range from as high as 25,000 to as low as 6,000. Historians agree that about 90 percent of Bund members were immigrants who arrived in America after 1919. In Wisconsin, the most heavily German state, the Bund seems to have mustered barely 500 members, which would rule out the possibility of anywhere near 25,000 members nationwide.

Ironically, the Bund’s goal of awakening Germans in America actually weakened German culture where it had once thrived. The Holocaust, the lack of new immigrants after the war, and suburbanization hurt, but the mere existence of the Bund had forced many German Americans to emphasize the American part of their identities and sacrifice the German.

National Archives photos

Copyright 2007 by 310 Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

FOLLOW US »