By Allyson Patton

The natural beauty of Hawaii—volcanic mountains, lush vegetation, and crystal water—should be Pearl Harbor’s main attraction, and it would be, if not for December 7, 1941. Instead, the island of Oahu’s stunning scenery has become merely the backdrop for the USS Arizona Memorial, a hallowed historic site that reminds us that 2,390 Americans died on a balmy morning 65 years ago when Japan attacked seven military sites in and around the harbor. Twenty-one ships were sunk or damaged, including the battleship Arizona. At 8:06 a.m., a 1,760-pound bomb slammed into the Arizona’s forward decks and ignited 500 tons of explosives in the powder magazine. She sank in nine minutes and burned for two days. A total of 1,177 men died on board, the greatest death toll ever on a US warship. Only 229 bodies were recovered. The rest remain entombed in the wreckage.

The natural beauty of Hawaii—volcanic mountains, lush vegetation, and crystal water—should be Pearl Harbor’s main attraction, and it would be, if not for December 7, 1941. Instead, the island of Oahu’s stunning scenery has become merely the backdrop for the USS Arizona Memorial, a hallowed historic site that reminds us that 2,390 Americans died on a balmy morning 65 years ago when Japan attacked seven military sites in and around the harbor. Twenty-one ships were sunk or damaged, including the battleship Arizona. At 8:06 a.m., a 1,760-pound bomb slammed into the Arizona’s forward decks and ignited 500 tons of explosives in the powder magazine. She sank in nine minutes and burned for two days. A total of 1,177 men died on board, the greatest death toll ever on a US warship. Only 229 bodies were recovered. The rest remain entombed in the wreckage.

A visit to the USS Arizona Memorial begins on shore in the open-air lobby of the visitor center, where each person receives a numbered ticket. The tour is free, and the ticket is a reservation for a 23-minute documentary on the attack. The wait to get into the theater can be long, but there is plenty to see in the meantime. An audio tour is available here for $5 and is worth the money. Actor and navy veteran Ernest Borgnine provides the narration for 23 stops.

With the exception of the theater, all the public buildings are open-air, which limits the display of artifacts. Even so, there’s a lot here. Black-and-white photographic murals depict the attack, the burning aftermath, and the struggling men, providing a big-picture perspective, while smaller items tell quieter stories of individuals. In a letter here dated May 22, 1941, for instance, Bud Heidt asks his mom if she has received the Mother’s Day card he sent her. He and his twin brother Wesley served aboard the Arizona. Seven months later both were killed in the attack.

Of all the attractions at the visitor center complex, the biggest draw is the Pearl Harbor survivors. Sometimes they approach to offer help or tell a snippet of a story. Other times they wait almost shyly for questions. Navy corpsman Sterling Cale was coming off night duty from the shipyard dispensary on the morning of Decem-ber 7 when he saw the attack begin. He spent four hours rescuing sailors from the burning harbor waters. When asked why he volunteers at the memorial, he answers, “Because I want to bring the story of December 7 to all the young people, so they know the story and never forget.” For some of the survivors, volunteering is therapy. Richard Husted was on liberty when his ship, the USS Oklahoma, was hit and capsized, taking more than 400 men down with her. “The fact that I was not aboard disturbed me for many a year…,” he says. “Being out at the memorial as a volunteer is sort of a catharsis, because I wasn’t there when it happened.” These veterans are a rare treasure and an invaluable resource that is quickly slipping away. According to the National Park Service, which operates the USS Arizona Memorial, more than 1,000 World War II veterans die each day.

Of all the attractions at the visitor center complex, the biggest draw is the Pearl Harbor survivors. Sometimes they approach to offer help or tell a snippet of a story. Other times they wait almost shyly for questions. Navy corpsman Sterling Cale was coming off night duty from the shipyard dispensary on the morning of Decem-ber 7 when he saw the attack begin. He spent four hours rescuing sailors from the burning harbor waters. When asked why he volunteers at the memorial, he answers, “Because I want to bring the story of December 7 to all the young people, so they know the story and never forget.” For some of the survivors, volunteering is therapy. Richard Husted was on liberty when his ship, the USS Oklahoma, was hit and capsized, taking more than 400 men down with her. “The fact that I was not aboard disturbed me for many a year…,” he says. “Being out at the memorial as a volunteer is sort of a catharsis, because I wasn’t there when it happened.” These veterans are a rare treasure and an invaluable resource that is quickly slipping away. According to the National Park Service, which operates the USS Arizona Memorial, more than 1,000 World War II veterans die each day.

On a good day (and most days in Hawaii are good), the waters beneath the memorial structure itself are sun-dappled and sparkling. A quarter-mile boat ride from the shore, the memorial measures 184 feet long and spans the wreck of the Arizona at just about midship. It is white and sepulchral with pristine lines, though still and peaceful rather than morbid. Inside, visitors can stop and take in the view of the harbor and the ship below them. The gaping maw of turret number three dominates one perspective. Not far from there is an open shaft with a corroded, twisted ladder inside. At the bottom lie flowers and wreaths, the only things visitors are allowed to drop into the harbor waters. That doesn’t prevent people from accidentally dropping brochures or the occasional digital camera, however, or even from purposely tossing in well-meant mementos. To prevent damage to the ship and marine life, divers descend twice a month to retrieve whatever visitors have left behind.

On a good day (and most days in Hawaii are good), the waters beneath the memorial structure itself are sun-dappled and sparkling. A quarter-mile boat ride from the shore, the memorial measures 184 feet long and spans the wreck of the Arizona at just about midship. It is white and sepulchral with pristine lines, though still and peaceful rather than morbid. Inside, visitors can stop and take in the view of the harbor and the ship below them. The gaping maw of turret number three dominates one perspective. Not far from there is an open shaft with a corroded, twisted ladder inside. At the bottom lie flowers and wreaths, the only things visitors are allowed to drop into the harbor waters. That doesn’t prevent people from accidentally dropping brochures or the occasional digital camera, however, or even from purposely tossing in well-meant mementos. To prevent damage to the ship and marine life, divers descend twice a month to retrieve whatever visitors have left behind.

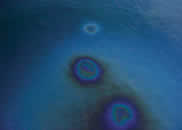

Another environmental concern here is the oil that seeps from the sunken ship. The Arizona had 1.4 million gallons of fuel on board when she went down, and perhaps half a million gallons remain. About a quart and a half a day bubbles up from below. Pearl Harbor survivors call the seepage “black tears.” It’s eerie to see and, in a strange way, a seemingly tangible connection to those who lie below.

The shrine room is the heart of the memorial. Here the names of the 1,177 servicemen who died aboard the Arizona are engraved on a white marble wall. 337 members of the crew survived the attack, and they too are remembered here when they die. Any Arizona survivor who wishes to be buried with his shipmates can have his ashes interred in the wreckage. To date, more than 24 interment ceremonies have been held here. According to park historian Daniel Martinez, “The story may have happened almost 65 years ago, but when we do a reburial, it’s December 7, 1941.”

On any given summer day some 4,500 people visit the USS Arizona Memorial. The current visitor center was not designed to accommodate so many, and some days as many as 1,500 people have to be turned away. To make matters worse, the building was constructed on a landfill and is now sinking at an alarming rate. But there is good news. A larger and better visitor complex is in the works. Construction on the $34-million project is scheduled to begin in August 2007 and end in February 2009. The memorial will remain open during the work, with tents temporarily replacing the current buildings. The new center will feature climate-controlled museum facilities. Though it will be a shame to lose the open-air facilities, the opportunity to see the thousands of treasures now kept under wraps due to lack of space and lack of climate control is more than an even tradeoff.

On any given summer day some 4,500 people visit the USS Arizona Memorial. The current visitor center was not designed to accommodate so many, and some days as many as 1,500 people have to be turned away. To make matters worse, the building was constructed on a landfill and is now sinking at an alarming rate. But there is good news. A larger and better visitor complex is in the works. Construction on the $34-million project is scheduled to begin in August 2007 and end in February 2009. The memorial will remain open during the work, with tents temporarily replacing the current buildings. The new center will feature climate-controlled museum facilities. Though it will be a shame to lose the open-air facilities, the opportunity to see the thousands of treasures now kept under wraps due to lack of space and lack of climate control is more than an even tradeoff.

This December, the site will host a 65th anniversary symposium with historians and a number of Pearl Harbor survivors. Martinez says it may be the last gathering of the old warriors and encourages people to attend. The attack on Pearl Harbor was “one of those moments where, literally, the plates of history slipped,” Martinez says, “and it changed us overnight.” The USS Arizona Memorial appears ready to carry on as a reminder of that earth-shaking event and the people who lived through it, long after those survivors are gone.

TRAVEL TIPS

Location: The USS Arizona Memorial is in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Hours & admission: Open 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day except Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day. Admission is free.

Information: Call 808-422-0561 to hear a recorded message or 808-422-2771 to speak to a museum staff member, or visit www.nps.gov/usar.

Copyright 310 Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

FOLLOW US »