Never mind that the 1944 story was set on another planet. The deadly bomb of the evil Sixa powers sounded too much like the Manhattan Project’s biggest secret.

By Richard Sassaman

If this were 1944, I’d be in big trouble for telling you this story. Secrecy is a dark but expected feature of wartime, and never was it taken more seriously than during the Manhattan Project—America’s race to create the ultimate war-ending weapon ahead of her Axis enemies. In that tense atmosphere, one science fiction magazine dared to publish a fictitious but detailed article about an atomic bomb on another planet—so detailed that military intelligence agents would be assigned to investigate everyone involved with the story.

If this were 1944, I’d be in big trouble for telling you this story. Secrecy is a dark but expected feature of wartime, and never was it taken more seriously than during the Manhattan Project—America’s race to create the ultimate war-ending weapon ahead of her Axis enemies. In that tense atmosphere, one science fiction magazine dared to publish a fictitious but detailed article about an atomic bomb on another planet—so detailed that military intelligence agents would be assigned to investigate everyone involved with the story.

It was in 1939 that tremulous whispers about the A-bomb first began to circulate in the United States. That year, in a lecture at New Jersey’s Princeton University, Danish physicist Niels Bohr revealed that two German scientists had published results in Europe of their experiments with uranium fission, the A-bomb’s atom-splitting process. Alarmed by the possibility that fascist Germany might succeed in manufacturing an atomic bomb, Hungarian refugee physicist Leó Szilárd wrote a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt. Another refugee physicist, German-born Albert Einstein, also signed the letter, which was delivered to Roosevelt in October. The letter urged that the United States begin research aimed at creating nuclear weapons, in case the Nazis were attempting to do so.

Most of two years passed before the United States established its A-bomb program, creating the Office of Scientific Research and Development in May 1941. Under the direction of Vannevar Bush of the Carnegie Institution of Washington (DC), the office began assembling teams at prestigious research universities such as Columbia, Princeton, Chicago, and California to conduct fission research. The process took on a new urgency after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Most of two years passed before the United States established its A-bomb program, creating the Office of Scientific Research and Development in May 1941. Under the direction of Vannevar Bush of the Carnegie Institution of Washington (DC), the office began assembling teams at prestigious research universities such as Columbia, Princeton, Chicago, and California to conduct fission research. The process took on a new urgency after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

In August 1942, the atomic bomb research program officially became the Manhattan Project. The name—inspired by the Manhattan District of the US Army Corps of Engineers in New York City, which would construct the first atomic-bomb plants—was deliberately bland. An army general had suggested calling the program the Development of Substitute Materials Project, but even this prosaic title was considered too likely to raise suspicions.

Manhattan Project scientists working at the University of Chicago under the direction of Enrico Fermi produced the world’s first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction in December 1942. Like Szilárd and Einstein, Fermi, whose wife was Jewish, was a refugee. He had fled from fascist Italy to America in 1938, almost immediately after winning the Nobel Prize.

Following Fermi’s success in Chicago, US efforts shifted from experimentation to physically building a bomb. More than 30 top-secret research laboratories throughout the country were involved. The three largest were unnamed secret cities that had been built on land taken over using the right of eminent domain. Site W—560 square miles in Hanford, Washington—and Site X—93 square miles in Oak Ridge, Tennessee—produced plutonium and enriched uranium for the bomb. Assembly would be done at Site Y—a laboratory covering 43 square miles in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

The Manhattan Project ultimately employed 130,000 people and cost nearly $2 billion ($21 billion in today’s money). Yet no one was supposed to know of it or talk about it. It was the biggest, most expensive secret in the world.

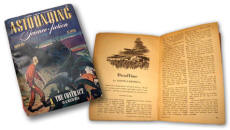

Imagine the US government’s surprise, then, when the short story “Deadline” appeared in the March 1944 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. Written by little-known freelance author Cleve Cartmill, the story describes how the evil Sixa powers, Ynamre and Ytal, have developed a terrifying new super bomb in a laboratory in the city of Nilreq, using cadmium, radium, and uranium. (Throughout his tale, Cartmill delights in spelling words backwards. Change the last letter of Nilreq to a b, reverse the name, and you’ll get the idea. “Sixa” is Axis, “Ynamre” is Germany, etc.)

The hero of Cartmill’s story is commando Ybor Sebrof, who has been sent from Seilla to destroy the bomb and thus defeat the Sixa powers. Sebrof reports that “U-235 has been separated in quantity sufficient for preliminary atomic-power research and the like. They get it out of uranium ores by new atomic isotope separation methods; they now have quantities measured in pounds.” If his mission should fail, he says, Nilreq “could end the war overnight with controlled U-235 bombs.”

To the average reader of the time, the tale would have seemed mildly entertaining, or perhaps downright preposterous. Science fiction author Robert Silverberg notes that “Deadline” ranked last among the six stories the magazine published that month. “It was not a particularly distinguished story,” he wrote. “It was, in fact, a klutzy clunker.” The story is predictable, shallow. It is set on another planet. Sebrof even has a prehensile tail. And the mad scientist Dr. Sitruc couldn’t be more of a cliché when he announces, “I have control of the greatest explosive force in world history, and my whims are obeyed as iron commands.”

Sebrof surely has a point, though, when he reports, “Our minds can’t conceive the unimaginable violence [of such a U-235 bomb] which might very well destroy all animate life. It’s a queer picture to think about.… Not a bird in the sky, not a pig in a sty. Perhaps no insects even.”

No matter how ridiculous the plot, US intelligence wasn’t laughing. The story’s detailed descriptions of powdered uranium oxide, or a fuse “in a tiny can of cadmium alloy containing a speck of radium in a beryllium holder,” were much too close to the nuts-and-bolts reality of the Manhattan Project. And what about this exploding U-235? At the beginning of March, the War Department sent an investigator from the Counter-Intelligence Corps to the offices of Astounding to speak with editor John W. Campbell.

Known today as Analog Science Fiction and Fact, Campbell’s magazine was founded in 1930 as Astounding Stories. Campbell took over in 1937 and a year later changed the publication’s name to include the words Science Fiction. He remained in charge until his death in 1971, and was considered to be the most important figure in the development of science fiction, an influence on famous writers such as Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein. The annual award for the best science fiction novel is named for him.

In 2003, Robert Silverberg, winner of the 1973 Campbell Award, used declassified records from the official government investigation of “Deadline” to write a two-part article for Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine. Campbell was upset during the war, Silverberg says, because his best writers had been lost to the war effort and he had almost no stories to publish. Cartmill suffered from polio and could not be drafted, so he was available. Campbell suggested he write a fantasy about atomic weapons, which, he informed Cartmill, were “fact, not theory.”

Campbell had studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was well read in technical literature. He knew about chain reactions and atomic weapons. So, he was able to provide answers when Cartmill asked hard technical questions such as “Wouldn’t the consequent explosion set up other atomic imbalances…until the whole damned planet went up in dust?” and “Isn’t [the bomb], once it has been assembled, trying each instant to blow itself apart?”

When the military investigators visited his office, Campbell explained all this, showing them that the “Deadline” story’s supposedly secret technical information had been available to the general public since 1940. (He could also have mentioned that Astounding had previously published other stories about atomic energy, including Heinlein’s “Blowups Happen” in September 1940 and Lester del Rey’s “Nerves” in September 1942.) Campbell readily supplied Cartmill’s California address, which the investigators forwarded to the local police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Neither had any information about Cartmill.

With little to show for their efforts so far, the investigators rolled up their sleeves. According to Silverberg, an intelligence report dated March 20, 1944, shows they enlisted the man who delivered Cartmill’s mail to conduct a seemingly casual interrogation. The postman, a science fiction fan, said he struck up a conversation about “Deadline” and found that Cartmill took credit for all the scientific research in the story himself, saying he possessed “a fair working knowledge of physics.” Beyond that, the postman reported, Cartmill was mostly interested in talking about a story he had just sold to Collier’s, a much higher-paying magazine.

By early May 1944, the investigation still had gone nowhere. The best the investigators could dig up was that Cartmill’s father had invented a new type of machine gun just before the war started, pitched it unsuccessfully to the US War Department, and then tried to sell it to the Japanese. It was merely intriguing coincidence—like the fact that Cartmill lived outside Los Angeles in Manhattan Beach.

Finally, a lieutenant colonel in the government’s Intelligence and Security Division at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, wrote to a lieutenant colonel in the Military Censorship Department in Washington, DC, saying he’d decided that Cartmill’s story was “not considered a violation of code of the wartime practices for publication” because it was fiction. Still, he continued, the story implied that the United States was conducting nuclear research and hoped to build atomic bombs, and such talk could “well provoke public speculation.” He suggested that Campbell be told to reread the Code of Wartime Practices that had been sent confidentially to editors and broadcasters in 1943, telling them to avoid mentioningsubjects such as “atom smashing, atomic energy, atomic fission, atomic splitting, or any of their equivalents.” If Campbell failed to comply, perhaps his all-important periodicals-rate postage permit would expire.

The lieutenant colonel in Washington, in turn, contacted someone in the government’s Office of Censorship who spent, as he put it, “an unpleasant half-hour” reading Cartmill’s story. Campbell was then told, in so many words, “Don’t do it again.” Not until August 6, 1945, when the Enola Gay dropped her 8,900-pound uranium bomb Little Boy on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, would the great and terrible secret of the Manhattan Project be revealed.

The “Deadline” story, writes Silverberg, “is often cited today as an example of science fiction’s ability to predict the future.” In fact, “it did no such thing. It simply recycled existing data.”

Cartmill himself, who died in 1964, probably would not argue with Silverberg’s assessment. Apparently, he never thought his atomic-bomb tale was particularly prescient. In fact, he seemed not to think much of the story at all. While he was unwittingly being interrogated by his postman that day in 1944, he nonchalantly offered his frank assessment: it “stinks.”

Image credits: Illustration by Paul Orban for Astounding Science Fiction, March 1944; magazine courtesy of Robin Becker, Richmond, Virginia; cover copyright 1944 Astounding Science Fiction, reprinted by permission of Dell Magazines, a division of Crosstown Publications.

Copyright 310 Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

FOLLOW US »